Sermon 34

Fast

Matthew 6:16

February 25,

2009

Sisters and

brothers in Christ, grace and peace to you, in the name of God the

Father, Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Today is Ash Wednesday, which begins the 40 days of Lent, which is the time before the celebration of our salvation on Good Friday and Easter. These days of Lent are marked by ashes and fasting – both of which help us to draw closer to God.

Rekindle

Your Faith

Lent is the time in the church year for renewing our faith, so that our praise on Good Friday and Easter may be genuine – in “spirit and truth” (John 4:24). This is how we draw closer to God. “Rekindle the gift of God,” we’re told (2 Timothy 1:7). And with the disciples we say to the Lord, “increase our faith” (Luke 17:5). We need this increase so that we will “never flag in zeal” (Romans 12:11). We need to grow in grace (2 Peter 3:18) so that we will keep pressing on to the “upward call of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:14). We need all of this to move ahead as we should – for, as Martin Luther (1483-1546) taught, our life with God “should be one that continually develops and progresses” [The Book of Concord (1580), ed. T. Tappert (1959) p. 449].

While God is

“at work in” us to bring all of this about, we still need to push ahead

“in fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12-13). This is because our faith

needs improving (2 Corinthians 13:9). Therefore we must supplement it

with “virtue, knowledge, self-control, steadfastness, godliness,

brotherly affection and love” (2 Peter 1:5-7). We need to “grow up to

salvation” (1 Peter 2:2). As Luther again taught, we must continually

purge “whatever pertains to the old Adam... in us our whole life long” (BC,

p. 445). Ashes and fasting are designed to help us do just that. They

help us draw closer to God, so that he can then draw closer to us (James

4:8).

Ashes

So today we have ashes rubbed on our

foreheads with Genesis 3:19 read over us: “Remember that you are dust,

and to dust you shall return.” We say and do this to be reminded of our

mortality and our wickedness – two things we would just as soon ignore

and even deny. It’s no surprise, then, that we think these ashes are

messy and foul. Why then do we use them? What’s the rationale behind

their use?

First, they are used to remind us that we are dying and that one

day we’ll be gone. We’re but a mist (James 4:8) – and we’re wasting away

(2 Corinthians 4:16). Naked we came into this world, and naked we will

pass out of it (Job 1:21). That means no one is immortal (Hebrews 9:26)

– regardless of what young, virile men on the battlefield may think –

which makes them “a bit mad” [Steven Pressfield,

The Virtues of War (2004) p.

182]. And like that rambunctious defiance on the battlefield, the more

benign version of it is sheer, simple denial. In his Pulitzer prize

winning book, The Denial of Death

(1974), Ernest Becker explains that

this view is very popular today in the

widespread move-ment toward unrepressed living, the urge to a new joy in

the body, the abandonment of shame, guilt, and self-hatred. From this

point of view, fear of death is something that society creates and at

the same time uses against the person to keep him in submission.

This belittling of the fear of death –

however it is fashioned – is everywhere in the educated, industrialized

world. We want to be carefree about death because we don’t like the

starkness and gloom it brings. Thomas McGrath (11916-1990), the poet,

says [Death Song (1991) p.

109) this is in large part because we don’t like what he calls “the

language of the dead,” for in it there’s

No punctuation except a period.

In that dictionary –

Nothing.

Or a single noun.

Be that as it may, we must still counter this belittling of death – by keeping a more robust vision of it before our eyes.

Luther believed we could do that by realizing anew how our death differs from, say, that of a cow’s (Luther’s Works 51:238). Other animals die from disease, accident or injury, and at no real fault of their own – their deaths being a mere “temporary casualty” (LW 13:94). But when we die, it’s “a far greater calamity” (LW 13:94). In our deaths there is high drama. For when we die, we’re being punished for our sins (Genesis 2:17; Romans 6:23). In our deaths, God is punishing us “because of His wrath over sin” (LW 13:98), since sin is what “brings about death” (LW 28:208). That’s why death is our enemy and not our friend (1 Corinthians 15:26). So, in thinking about dying, we have to “contemplate... God’s wrath” (LW 13:99). And when we do we are consumed by it and “bear an intolerable burden because we know that God hates us on account of sin” (LW 13:106). Now it is just this thought that helps us when we’re “hounded” by it and “clubbed” with it (LW 13:93). Having ashes smeared on our foreheads is a way of letting death hound us, that the terror in God’s wrath might all the more grip us.

Fasting

On this day we also begin a fast (Joel 2:15; Matthew 6:16). To fast is to deprive ourselves of foods that we like. So we don’t give up spinach, for instance, during Lent – but only food that we crave – like chocolate covered almonds! And this we can do, for even researchers know that our appetites are “surprisingly elastic” [Michael Pollan, Omnivore’s Dilemma (2006) p. 106]. Even so, fasting isn’t easy. St. John Climacus (579-649) of old, in his classic, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, explains why fasting is so difficult:

Gluttony is hypocrisy of the stomach. Filled, it moans about scarcity;

stuffed, and crammed, it wails about its hunger.... [So] to fast is to

do violence to nature.... Fasting is... humble sighing, joyful

contrition,... a custodian of obedience.... [So] let us put a question

to [gluttony], this enemy of ours.... Let us ask this bane of all

men,... who her children are... Gluttony answers us: “... The reason for

my being insatiable is habit. Unbroken habit, dullness of soul, and the

failure to remember death are the roots of my passion.... My first son

is the servant of Fornication, the second is Hardness of Heart, and the

third is Sleepiness. From me flow a

Now regarding the fast itself, we believe that there isn’t just one set way to do it – like eliminating beef or some other “specified foods” (BC, p. 69). No, for us the point in fasting is instead simply to deprive ourselves of a favorite food – whatever it may be. What we cut out may be the same every day or vary from day to day – but it has to be something we especially like. So it’s up to each one of us to tailor our own plan for fasting during Lent – since we each have different tastes. But if you need a plan, here’s one to adopt or to modify in part. Remember that Sundays in Lent are not fast days. Now, in this plan you are first of all to eliminate all alcoholic beverages, carry-out and restaurant food throughout the forty days of Lent. And secondly you are to follow this schedule:

Mondays have only water and juice.

Tuesdays eat no beef, fish or fowl.

Wednesdays eat no sweets.

Thursdays cut what you eat in half.

Fridays eat just one meal.

Saturdays eat no beef or fowl.

This plan is for Lent (and Advent too, for that matter). But it does not mean that we don’t have to fast the rest of the year (BC, p. 69). Over the generations Christians have also fasted twice every week – on Wednesdays in observance of the betrayal of Christ by his friend Judas and on Fridays in honor of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross for sinners. So our Lenten fast is only an expansion of our regular, ongoing fast – not something altogether new.

But what is fasting really about? Is it some sort of veiled ecclesiastical dieting plan? What’s its tried and true purpose? Could it be a veiled evil – an eating disorder to rival bulimia and anorexia? No, not at all. It’s rather about practicing self-denial (Matthew 16:24) – which is at the heart of Christianity. And that is because of the wickedness that’s within us (Genesis 6:5-6; Jeremiah 17:9; Mark 7:20-23; 2 Timothy 3:2-5; Revelation 3:17). Fasting fights against that wickedness by putting “restraints on our flesh,... lest we... become complacent... and pamper the desires of our flesh” (BC, p. 221). If we were simple, unalloyed goodness, it would be a different matter. Then we wouldn’t have to fast or deny ourselves. But we aren’t innocent (Job 9:20, 28, 19:4, 29:14, 27:5) and so we must deny ourselves – and even lose our lives, hate ourselves and die to ourselves (Matthew 16:25; John 12:25, Romans 6:6). None of this is about self-mutilation or suicide – so don’t be misled. That would be to miss the point of it all – which rather is simply to love God and serve the neighbor (Matthew 9:37-38, 22:36-40). That’s why we deny ourselves – that we might love God and serve our neighbor. Self-denial, then, is about quitting living according to what we think will make us happy (2 Corinthians 5:15) – and obeying God instead. It means saying not my will be done, but God’s will be done (Matthew 6:10; 26:39). That’s the goal of self-denial and fasting. Anything else is a lie, a dodge, a contrivance.

The Bread of Life

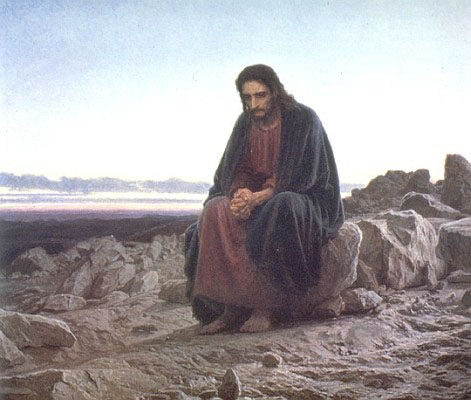

But even so, will we be able to reach this goal or even strive diligently for it? Or will we be crushed under its insurmountable weight? Is this goal pushing us too far? Can we actually believe that we are not to live “by bread alone” (Matthew 4:4)? Or will we hoard what we have (Luke 12:18) like God’s people did long ago in the wilderness – which lead to making their bread foul and full of worms (Exodus 16:20)? Will we gladly take on the ashes and keep the fast – or will we succumb, trying instead to make our bellies into our gods (Philippians 3:19)?

Jesus hopes not. In John 6:27 he encourages us not to “labor for the food which perishes, but for the food which endures to eternal life.” And where do we find such “supernatural” food (1 Corinthians 10:3-4)? Jesus says that we find it in him for he is “the bread of life,” and that whoever eats of him will “have eternal life” (John 6:35, 40). So he is the indispensable one – and “we must not look for God outside this Person” (LW 23:115). Without him we’ll fail and have no peace with God (Romans 5:1). Without him we’ll languish – regardless of what the famous American, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), taught us in his highly esteemed and often reprinted, 1841 essay, “On Self-Reliance” (see The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson, 2008). No, Luther instead had it right, that those who reject Christ as Lord and Savior

must either cherish this temporal life as the only thing worthwhile and hate to lose it, or they must expect that after this life they will receive eternal death and the wrath of God in hell and must fear to go there (LW 53:325-326).

This is because only the blood sacrifice of Jesus can save us from the wrath of God (Romans 5:9; Ephesians 5:2). On the cross he was “stricken, smitten by God and afflicted,” for it was the will of God to bruise him, that by his wounds we might be saved (Isaiah 53:4-5, 10; Acts 2:23; 1 Peter 2:24). As strange as it may seem, salvation is only possible if God makes Jesus “become poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Corinthians 8:9). In this imposed poverty, Jesus becomes “sin who knew no sin” (2 Corinthians 5:20), that he might be punished for our sins (Isaiah 53:5; 1 Peter 2:24; Galatians 3:13; LW 26:284; BC, p. 562).

So while we struggle to begin the fast with ashes on our foreheads, we must remember the true bread, Christ Jesus our Lord – knowing full well that “new life comes by faith amid penitence” (BC, p. 164). Do this even though it seems “senseless and meaningless” (LW 23:45) to call him bread. No, this bread is no ordinary meal, it’s rather spiritual food that requires “spiritual eating” (LW 23:116). So when you eat of him you are imbued with a “godlike power [to] wipe out your sin [and] deliver you from death” (LW 23:122). No wonder, then, that he’s the bread of life (John 6:35). So to feast on him is not like “feasting on beef or veal at a wedding” (LW 23:42). No, feasting on Christ means believing in him “who is... the bread of life” (LW 23:112). And this feasting, this believing, opens up the way to eternal life (John 6:40, 51).

So praise God for the Savior Jesus Christ – for in him is life (John 6:53-54). Praise God for the faith he has given you through water and the Spirit (John 3:5) – for it’s only through faith that you have this life in the first place (John 3:16; Romans 3:25; Ephesians 2:8). And then call on God to help you “fight the good fight of faith” (1 Timothy 6:12), that you might not suffer from “an evil, unbelieving heart” which would lead you to “fall away from the living God” (Hebrews 3:12).

The Body of Christ

And during Lent, let us also increase the honor due to our “most venerable sacrament” (BC, p. 577) – the Lord’s Supper. This is the body of Christ for us – “in and under the bread and wine” of this sacrament (BC, p. 447). We are not to think of this Supper as “a mere feast,... as if it were nothing but an ordinary meal” (LW 37:343). No, it’s a sacrament or a mystery (LW 36:94) more than a meal, and so it serves up only morsels of bread and sips of wine. No guzzling or stuffed bellies here (1 Corinthians 11:33-34). Just bird’s portions – and nothing more. So this feast is something of a fast, which on the surface conflicts with its celebratory nature. But in Matthew 26:29 Jesus says he will not eat of this meal with us again “until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.” So this meal has curbs placed on it by its very own Master. And because it’s not unfettered – it is something of a fast.

Therefore Luther rightly calls this sacrament “a taskmaster by which we order our lives and learn as long as we live” (LW 36:353). This corrective feature is there in 1 Corinthians 10:21 where it says it’s incompatible with the table of demons. This sacrament, then, requires of us to live contrary to the way of the demons. So it’s not just some spiritual sop that washes away all of our problems. No, it rather blesses us in two quite different ways.

First, “all the power” (LW 26348) in this sacrament lies in what Jesus gives us – “his body and blood on the cross to be our treasure and to help us... receive forgiveness of sins,... that we may be saved [and] redeemed from death and hell” (LW 36:352). That’s why this sacrament is not for those who are completely sinless – as if that were even a possibility. No, it’s rather “a food for hungry and thirsty souls, who feel their misery and would gladly be rescued from death and all misfortune” (LW 36:351). Nevertheless it’s also true that we are to be

pure in the sense that we are sorry for our sins and would gladly be rid of them, and are vexed that we are such miserable people – in so far as we are serious about it and not just pretending (LW 36:351-352).

This teaching about our salvation “is the first principle of Christian doctrine” (LW 36:352). No wonder we are to be serious about it. And even though this salvation was permanently set forth long ago (John 19:30), it must still be “set before us... anew each day.” We must “be on guard,.... build firmly on these words and stand fast in them (LW 36:352, 351).

And secondly we are “to give ourselves with might and main for our neighbor.... That is how a Christian acts.... He makes no distinction, but helps everyone with body and life, goods and honor, as much as he can” (LW 36:352, 353). Because God so loved us, we should also “love one another” (1 John 4:11). For this reason this sacrament is also known as “communio, that is, a communion” (LW 36:352). For by being united with Christ we are also united with “his saints and [have] all things in common with them” (LW 35:52). In this sacrament our sins are forgiven, “as we forgive others” (Matthew 6:12). In this sacrament we learn humility, by counting others “better than ourselves” (Philippians 2:3). If God loved us while we were yet sinners (Romans 5:8), then we also ought to love others even if they’re not our friends (Luke 6:36). These admonitions stretch us to the breaking point. No wonder, then, that this sacrament has enough in it to “occupy us all our lives” (LW 36:353).

Let us then cherish and cling (LW 23:128) to this most venerable sacrament during these days of Lent. Let us do so remembering a story Luther told from 1530:

There was a certain man... who... did not go to the sacrament on the shameful pretense of Christian liberty.... When he began to feel that the end of his life had come, he called for the chaplain and asked for the sacrament. Just as the chaplain brought it to him and placed it in his mouth he died, and the sacrament remained on the tongue of his opened mouth so that the chaplain had to take it back again. He was upset that he had to take it back, and when he asked me where he should put it, I told him to burn it. Dear fellow, let this be an example... for you that you do not live a dissolute life.... [For] if you can despise God in his sacrament, he can in turn despise you in your needs (LW 38:135). Amen.

(printed as preached but with

some changes)