Sermon 31

Endure

Matthew

24:13

November 16,

2008

Sisters and

brothers in Christ, grace and peace to you, in the name of God the

Father, Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen.

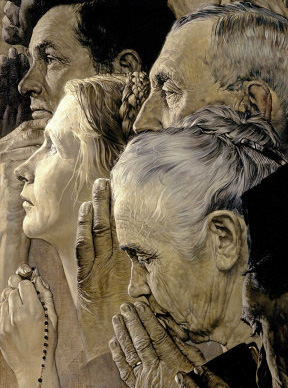

Matthew 24:13 says whoever endures to the end will be saved. Why does our Lord Jesus say that? Why does he want us to hang in there, not give up, keep our nose to the grind stone and toe the line? Why does he want us to tough it out and endure – endure, endure to the end? Why all of this pressure on us?

Giving Up So

Quickly

No, matters in this life are up for grabs – that’s why we are to work out our salvation in “fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12), with all spiritual cockiness purged from us (1 Corinthians 10:12). As long as we live, it remains uncertain whether or not we’ll “continue in the faith” (Colossians 1:23; Luke 17:5, 18:8). And if we are to be saved, we must do just that – believe to the end (John 3:16; Revelation 2:10). It is therefore wrong of us to suppose that it’s “enough merely to accept the Gospel, [for] acceptance must be followed by that spiritual power which renders faith firm... in conflicts and temptations” (Sermons of Martin Luther, ed. N. Lenker, 8:267). We must “lead the life of active soldiers” (Luther’s Works 20:8) for by such pugilistic, spiritual efforts we are then able “to remain steadfast” (LW 13:177). We must not willingly remain “hardened, impious [and] insensitive” (LW 25:478).

So beware. Don’t forget Alexander and Hymenaeus who made a “shipwreck of their faith” (1 Timothy 1:20). The same could happen to you. And this can also come about quietly by “drifting away” from so great a salvation (Hebrews 2:1-3). How ghastly!

Grievously

Tempted

The reason our faith gives way is because we shamefully give in to temptations. And they’re all around us – as well as within us. The devil, we are told, prowls around like a lion, seeking to devour us (1 Peter 5:8). And as if that were not enough, from within us also come all sorts of evils which defile us, “reptilian thoughts” (LW 51:25), as Luther called them – such terrible things as pride and foolishness, fornication and murder (Mark 7:20-23).

We are vulnerable to these temptations because we fear people instead of God. Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), whom we remember this time of year – thanking God for his abiding witness to the riches of Christ Jesus – aptly describes these false fears:

Instead of impressing upon [one another] a holy fear and a sense of shame before the good, [we teach others] to fear financial loss, loss of reputation, lack of appreciation, disregard, the judgment of the world, the mockery of fools, the laughter of light-mindedness, the cowardly whining of obeisance, the inflated insignificance of the moment, the delusive, misty apparitions of miasma [or swamp gases] (Kierkegaard’s Writings 15:58).

These false fears make us “effervesce,” Kierkegaard says, and we then end up loving the moment, fearing time and counterfeiting eternity – by turning it into “the deceptive illusion of the horizon,... the bluish boundary of time,... [and] the dazzling jugglery of the moment” (KW 15:62-63).

Deeply

Distracted

Kierkegaard further explains that these temptations are so deep, that they are even rooted in time itself:

Alas, time and busyness think that eternity is very far away, and yet in drama the producer has never at any time had everything in readiness for the stage and the transformation of the performers in the way eternity [or God] has everything ready... at every moment – although it holds back (KW 15:66).

Time nit-picks our souls to death with its myriad distractions. We have lists of things to do each day – and none of what we write down has anything to do with eternity. Time not only envelops us – but it also seem to consume us. We can’t get free of it and we can’t save ourselves from it either. Time is a strange thing to talk about – and yet we must because eternity is at stake. The temporal flow tries to rob us of eternity. Kierkegaard says it tries to make us think that eternity is very far away. “Goaded on,” he continues,

in superstitious delusion one would rather hope for [temporality’s help] than grasp the eternal.... Ah, it is a foolish sagacity (however much it swaggers, however loquacious it is) that foolishly defrauds itself out of the highest comfort and by means of a mediocre comfort helps itself into an even more mediocre comfort, and ultimately into certain regret (KW 15:114).

No wonder we’re told not to set our minds on earthly things, but on the things that are instead above (Colossians 3:2).

No Ability

Implied

Yet even with this clarification and authorization for the call to endure, we still find ourselves waffling. It’s clear that we are to endure, but we cannot seem to pull it off – the good that we would do, we just can’t do (Romans 7:18). Why, then, are we told to do it? Is this command itself somehow incoherent? Or is it just sheer mockery of our miserable incapacities?

Well, actually, it’s neither. This is because commands in Christianity do not imply ability – by necessity. That is to say, just because we’re told to do something, does not mean we can. Now if that is so, then why are we told to do it in the first place? The sense in all of this seems to escape us – to say the very least. So what’s up? How should we understand these Biblical commands?

In Christianity commands don’t act normally but function differently. Luther explains their unusual purpose in this way:

Moses... issues commandments about doing, but does not describe man’s ability to do. The inference tacked on by [foolish reason] however concludes: Therefore man is able to do such things, otherwise they would be commanded in vain.... [But this] reasoning is bad.... [For] the commandments are not... either inappropriate or purposeless, but are given in order that blind, self-confident man may through them come to know his own diseased state of impotence if he attempts to do what is commanded (LW 33:128).

Our inability is therefore to lead us to despair over our own infected or disordered capacities (KW 22:54), so that we might long for someone else – who is stronger – to save us (Romans 7:24-25).

The

Steadfastness of Christ

Our failure to do what we should do could easily drive us to despair and unbelief. We could lament our failure and end up with “darkness” as our only companion (Psalm 88:18). But that malaise is not the only possible outcome. From early on the hope has instead been that we’ll be driven to Christ (LW 16:232; 26:126).

And in our despair if we look to Christ we’ll learn that he is

the one who strengthens us so we can endure (1 Thessalonians 3:12-13) –

in spite of ourselves. And this he does by way of his “steadfastness” (2

Thessalonians 3:5). Great power is manifest in that steadfastness. We

first and foremost see this in his crucifixion. He was “obedient unto

death – even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). That resolve to

sacrifice his life for sin (Hebrews 9:26) takes great intestinal

fortitude. It takes sterling singleness of purpose. On the cross he was

taunted: “Save yourself!.... Come down from the cross.... and we’ll

believe in [you].... Let God deliver you now, if he desires you”

(Matthew 27:40-43). But Jesus doesn’t budge. He is not swayed by their

mockery. His face, after all, has been “set... to go to

And in his suffering and death, Christ will move “the Father to grace” (LW 51:277) so that “God is reconciled to us” [BC, pp. 121, 137, 140, 142, 147, 149, 152, 153, 165, 166, 216, 253, 257, 260; contra R. W. Jenson, Systematic Theology (Oxford, 1999) 2:187] by way of the stilling of his wrath (BC, p. 138). For indeed, Christ

was placed under the law for us, bore our sin, and in his path to the Father rendered to his Father entire, perfect obedience from his holy birth to his death in the stead of us poor sinners, and thus covered up our disobedience, which inheres in our nature,... so that our disobedience is not reckoned to us for our damnation but is forgiven... by sheer grace for Christ’s sake alone (BC, p. 550).

No wonder, then, that Kierkegaard erupts at the end of his 1848 book, Christian Discourses, saying: “I will seek my refuge with... the Crucified One,.... to save me from myself” (KW 17:280)!

And the second way Christ’s steadfastness helps us is by strengthening us now, in this life (1 Timothy 4:8). Christ’s victory becomes ours right now. It doesn’t just open the gates of heaven in the end (Hebrews 10:20), but helps us endure right now. This is a strange notion – since we know other important qualities, like the talent to play baseball, for instance, that cannot be shared. But Christ’s victory over “sin, death, God’s wrath, the devil, hell and eternal damnation” (LW 23:404) can be shared with us (2 Corinthians 4:14). Through this sharing, when we believe in his victory and entrust our lives to his care, he becomes “our righteousness,” though we remain “ungodly” (1 Corinthians 1:30; Romans 5:6).

With this strengthening, we, like

Lord,

Forgive Us!

In the face of our “spiritual fornication” (LW 25:346) with temporality and finitude (contra John 15:18-19), we must now repent of our filthy, sinful descent into time. This is because we were not made to be absorbed into time. So with Kierkegaard, we should sneer in the face of temporality, and query:

Why was an immortal spirit placed in the world and in time, just as a fish is pulled out of the water and cast onto the beach? (KW 15:62).

Therefore let us repent now. Let us crawl back into the water, as it were. Do not therefore “weary your soul with makeshift, temporary palliatives; do not grieve the spirit with temporal consolations” (KW 15:101)! Repent instead. All those temporal consolations do is make your mind vacillate between “drowsiness and a burning tension” (KW 15:112). Therefore repent, even though it isn’t popular. Kierkegaard puts it this way, on a related matter:

If adhered to it will make your life strenuous, many a time perhaps burdensome; if adhered to it will perhaps expose you to ridicule by others, not to mention that adherence might ask even greater sacrifices from you. It goes without saying that the ridicule will not disturb you, that is, if you hold fast to the conviction; the ridicule will even be of advantage to you also by convincing you even more that you are on the right path (KW 15:136).

So repent and bear the burden and the ridicule – you’re on the right path. And do that by praying to God to forgive you your sins.

Martin Luther, in his Large Catechism (1529), explains that prayer for forgiveness in this way:

There is great need to... pray, ‘Dear Father, forgive us...’ Not that he does not forgive sin... before our prayer.... But the point here is for us to recognize and accept this forgiveness. For the flesh in which we daily live is of such a nature that it does not trust and believe God and is constantly aroused by evil desires and devices, so that we sin daily in word and deed, in acts of commission and omission. Thus our conscience becomes restless; it fears God’s wrath and ... loses the comfort... of the Gospel. Therefore it is necessary constantly to [pray this prayer. This serves] God’s purpose to break our pride and keep us humble.... If anyone boasts of his goodness,... he should examine himself in the light of this [prayer]. He will find that he is no better than others, that in the presence of God all men must humble themselves and be glad they can attain forgiveness. Let no one think that he will ever in this life reach the point where he does not need this forgiveness. In short, unless God constantly forgives, we are lost. Thus this [prayer] is really an appeal to God not to... punish us as we daily deserve, but to... forgive as he has promised, and grant us a... cheerful conscience (BC, p. 432).

These powerful words will help keep you on the right path. For in them we have the motivation and requirements for forgiveness, as well as the dangers and fears clearly stated if it’s rejected and lost.

Abiding in

Christ

Now, all of you who have heard these words of Christ regarding his steadfastness, come to the Altar, bow down and received him this day – “in, with, and under” (BC, p. 575) the bread and the wine of the Lord’s Supper. Bow down knowing that “to be lifted up to God is possible only by going down” (KW 18:132). Know that when you receive this sacrament, Christ himself will abide in you that you may abide in him (John 6:56). And when you abide in Christ, his steadfastness will become yours as well. Rejoice in the strength it provides for you – making you “divinely strong in weakness” (KW 18:176). Do not doubt that it is here for you – “to bring... refreshment” (BC, p. 449). Know that in it there’s “abundant life” for you (John 6:53, 10:10) or zoe, ζωη, in the Greek. This isn’t sheer existing (βιος) – this is a rich life with God.

Welcome the

Prophets

And when you leave church today, do good works in Christ’s name. Practice what’s been preached. Live a life worthy of the Gospel you’ve heard today (Philippians 1:27). Follow Jeremiah 26:5 which says “heed... the prophets” whom God urgently sends. They are the ones who call us to greater faithfulness. They are the ones who insist that God wants us to live “a vastly higher life than others know” (SML 8:282). And rather than rejecting them and even killing them because of the pressure they place on us, let us simply bless them in the name of the Lord (Matthew 23:39).

And may we do the same with those prophets who have followed the Biblical ones and witnessed among us in our time. See them as your friends – even though they too bear down on you in order to hold your feet to the fire. Welcome them even though they press for greater dedication and discipleship (LW 26:99).

May we this day so regard Søren Kierkegaard, from

a great deal of Kierkegaard’s work is addressed to the man who has already become uneasy about himself, and by encouraging him to look more closely at himself, shows him that his condition is more serious than he thought.... Nobody except Christ and, at the end of their lives perhaps, the saints are Christian. To say “I am a Christian” really means “I who am a sinner am required to become like Christ.”

To that I say Amen – and again I say, Amen.

(printed

as preached but with some changes)